Forgotten Friday – Private Thomas Highgate

Private Thomas James Highgate was born on 13th May 1895 he was a British soldier during the First World War. Thomas was the first British soldier to be convicted of desertion and was executed by a firing squad on the Western Front.

Thomas was born in Shoreham and worked as a farm labourer before joining the army in 1913 as a seaman. When the First World War began, he fought with the First Battalion of the Royal West Kents. He was executed only thirty-five days into the war.

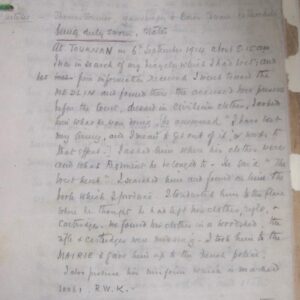

The battalion arrived in France on 15th August 1914 and fought in the Battle of Mons. By September 1914, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were in retreat. Forty-thousand British soldiers fought in the battle, and 7,800 were killed. On the morning of 6th September 1914, Highgate left the frontline, saying he needed to “ease himself”[1], and hid himself in a farmhouse. He was found by a gamekeeper, who was both English and a former soldier, while wearing civilian clothes and without his rifle. His army uniform was discovered nearby.

Terrence Highgate – BBC NEWS (c)

A Historian named Julian Putkowski[2] wrote that the total time of Highgate’s desertion was likely “no more than an hour or two”. Highgate reportedly found the fighting too horrific; he is recorded as having said to the gamekeeper, “I want to get out of it and this is how I am doing it”. He was arrested by the gendarmes and taken into custody by Captain Milward. Highgate told Milward that he did not remember having done anything except leave his bivouac shelter. In court, Highgate said that he remembered walking around, entering the farm, lying down in a civilian house, and putting on civilian clothes but did not recall much else.

Highgate was not the only soldier to act dishonourably during the retreat from Mons; two officers attempted to surrender their battalions to the enemy. They were discharged and did not face the death penalty. There were other instances of soldiers looting and travelling with civilians, as well as one allegation of rape. As a result, there were concerns about discipline throughout the British Expeditionary Force.

Thomas Highgate was unable to call members of his battalion as witnesses as they had all been killed, captured or injured during the Battle of Mons. He also did not have an officer to call as witness, despite that being his right. Two days later, on 8th September, he was executed by a firing squad consisting of men from the 1st Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment in the 15th Brigade[3]. Highgate died at 7:07, 45 minutes after he himself found out about his guilty verdict. Aged 19, Highgate was the first British soldier to be executed for desertion on the Western Front, 35 days after the war began.

WO-71-387-Highgate-witness-statements-Blog National Archives

Putkowski said that there may have been a “crisis of confidence” amongst senior officials in the army, who at the time of Highgate’s trial had seen the deaths of 20,000 men from the British Expeditionary Force and many others wounded or missing. Highgate’s death was used as a disciplinary tool for the army. General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien said that he “should be killed as publicly as possible”. Men from the 1st Battalion, Cheshire Regiment and 1st Battalion, Dorset Regiment witnessed the execution in person. Highgate’s death was also publicised in the army Routine Orders. According to the diary of General Smith-Dorrien, two men were executed on 7th September, one for plundering and another for desertion. Putkowski writes that the date must be a mistake on Smith-Dorrien’s part, as the recorded execution was most likely Highgate, and there is no evidence of a man being shot for plundering on that day. [4]

Highgate’s name was not included on the war memorial at Shoreham; from the late 1990s onwards, some residents fought for his name to be added whilst others disagreed. Posthumous pardons for soldiers who had been executed, including Highgate, were announced in 2006.

Read more here: ©

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-25841494

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Highgate

[1] McGowan, Patrick (14 March 2000). “Disgraced soldier is forgiven, 86 years on”. The Evening Standard. p. 9. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022.

[2] Putkowski & Sykes 1990, p. Chapter One: Regular blood.

[3] Putkowski & Sykes 1990, p. Chapter One: Regular blood.

[4] Ibid Putkowski