The London Naval Conference held on 22nd April 1930.

It was the third in a series of five meetings, formed with the purpose of placing limits on the naval capacity of the world’s largest naval powers. The purpose of the meetings was to promote disarmament in the wake of the devastation of the First World War. They began with the Washington Conference of 1921–22 and concluded with the London Conference of 1935. After an unsuccessful meeting in Geneva in 1927, Great Britain, the United States, Japan, France, and Italy gathered in London in 1930 to make a new attempt at revising and extending the terms of the Five Power Treaty of 1922.

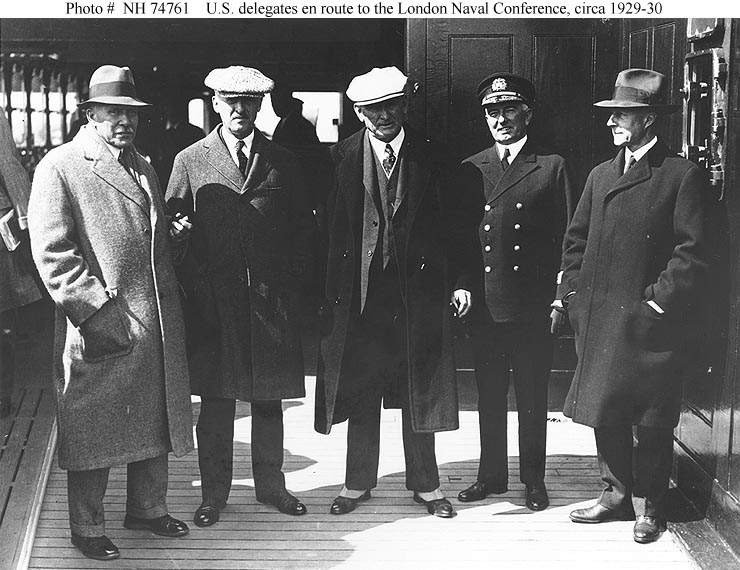

In 1927, Great Britain and the United States could not agree on naval cruiser limits; however, representatives of the two governments continued to work on a compromise measure. By 1930 both sides were anxious to reach a deal to avoid an all-out arms race. Therefore, forced their naval officers to take a back seat to their diplomats in the negotiations.

Ratifications were exchanged in London on 27th October 1930, and the treaty went into effect on the same day but were largely ineffective because of their disagreements.

The treaty was seen as an extension of the conditions agreed in the Washington Naval Treaty, an effort to prevent a naval arms race after the First World War. The conference was a revival of the efforts that had gone into the 1927 Geneva Naval Conference at which the various negotiators that had been unable to reach agreement because of bad feelings between the British and American governments. The problem may have initially arisen from discussions held between the US President Herbert Hoover and the Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald at Rapidan Camp in 1929, although, a range of factors affected tensions, which were exacerbated by the other nations at the conference.

Under the treaty, the standard displacement of submarines was restricted to 2,000 tons, with each major power being allowed to keep three submarines of up to 2,800 tons. Except for France who was only allowed to keep one. The submarine gun calibre was also restricted for the first time to 6.1 in (155mm) with one exception, an already-constructed French submarine being allowed to retain 8 in 203mm) guns. This put an end to the ‘big gun’ submarine concept. (This was a predeceasing issue dating back to the 1905 Naval Race.)

Although the treaty was described as an ‘arms limitation conference’ the London Naval Treaty set limits above the current capacity of some of the powers involved. The U.S Senate approved the treaty in July of 1930. Over the objections of key naval officers concerned that the naval limitations would inhibit the American ability to depend on its control of the Philippine islands. The United States embarked on a shipbuilding program to make up the difference between its existing cruiser tonnage and it was allotted under the treat. That building ultimately helped to alleviate some unemployment caused by the Great Depression.

In 1935, the powers met for a second London Naval Conference to renegotiate the Washington and London treaties before their expiration the following year. The Japanese walked out of the conference. However, Great Britain, France, and the United States signed an agreement declaring a six-year holiday on building large light cruisers in the 8,000 to 10,000 range. That final decision marked the end to the decade long controversy over cruisers.