Those That Stayed Behind: Conscientious Objectors and Scheduled Occupation during the First World War

WW1 Military Conscription

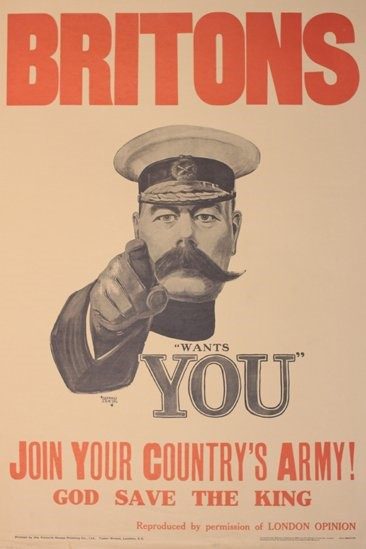

After the outbreak of war in July 1914, it became apparent that Britain’s small professional army would not be sufficient for the scale of conflict the country faced. Britain’s Secretary of State of War, Lord Kitchener proposed the formation of a new army, called ‘Kitchener’s Army’ which consisted solely of volunteers. At first, large quantities of men enlisted, driven by patriotism to serve their country that the army struggled to process the new recruits. Pacifists or those who were against the war due to religious or moral grounds were free to abstain from the war effort as it was personal choice.

In March 1916, the government passed the Military Service Act which classed all medically fit men between the ages of 19 and 41 as being liable for conscription. This was the first-time compulsory military service was introduced in Britain. It was necessary as the number of volunteers had decreased drastically since the start of the war, and volunteers could not replace the number of men that were being lost at war. In May of the same year, the British Government extended the Military Act to include married men and the age bracket was lowered to 18. Conscripted men had no choice on which service, regiment, or unit they joined. The passing of the act meant that for the first time, men who could not or would not support Britain’s role in the war were forced into public view.

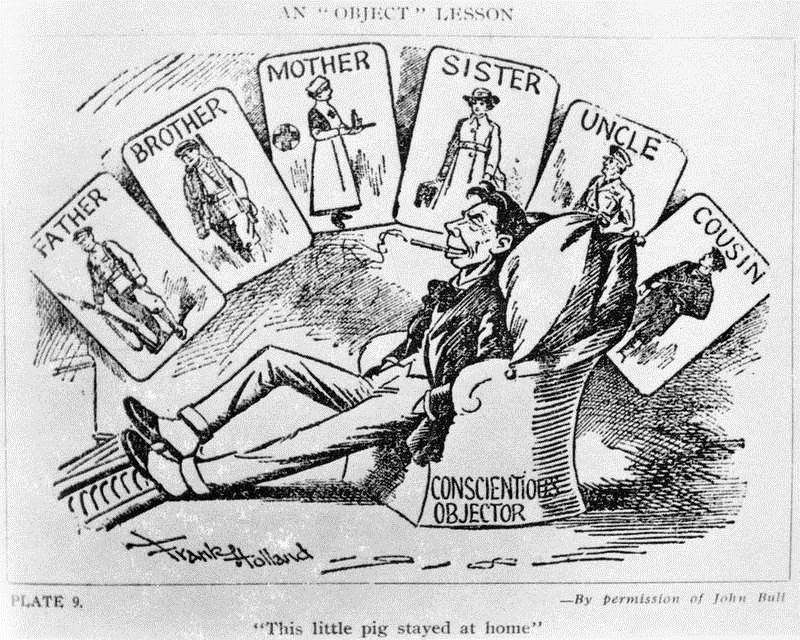

Conscientious Objectors

A conscientious objector (also called ‘Conchies’ or C.O.s) was a person who opposed joining the armed forces and or bearing arms due to moral or religious principles. There were approximately 16,000 British men on record as conscientious objectors to armed service during the First World War. The most common reason was on religious grounds. These men included Methodists, Congregationalist, and Quakers among others. Others opposers were political activists who saw the war as acting on imperialist motives and believed the working classes were being made to fight in a war orchestrated by the ruling classes. Humanists were against taking human life but not on religious grounds, while others simply objected to government intervention in their lives on a general level so naturally opposed mandatory conscription.

The Military Act included a ‘conscience clause’ which permitted men to object to conscription on such grounds. These individuals had to apply to military tribunals who could recommend non-combatant roles in the armed forces like in a medical unit, or civilian work such as forestry, factory, or hospital work. Many were ordered to join the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC) which was a military unit where they could work in support roles that did not involve fighting; these men were known as Alternativists.

Men who did not accept this compromise were known as Absolutists, as they demanded absolute exemption. They would offer their services in no capacity during the war and as a result were imprisoned and were sentenced to hard labour. In Hull, 541 tribunals were held over two years, dealing with 17,478 individual cases. The tribunals granted 14 absolute exemptions, 2,798 conditional exemptions and 1,687 temporary exemptions.

The Richmond Sixteen Court Martial

The Richmond Sixteen were a group of absolutist British conscientious objectors during the First World War. The men were imprisoned in Richmond Castle, North Yorkshire which was the base of the NNC and where COs were held. Their treatment was the same as criminal prisoners and the men were allowed very few censored letters or visitors. In May 1916, the army began sending companies of NCC men to France from camps across England and Wales, with the expectation that they would complete non-combatant work behind the lines. On 29th May, the Richmond Sixteen were taken from Richmond Castle and transported to Henriville military camp, near Boulogne, France. Once there, they refused their non-combatant duties and were threatened with the firing squad as they were classed as on active service. The men were lined up but after a hair-raising pause, there sentence was reduced to 10 years hard labour. The Richmond Sixteen were not the only absolutists to be sent to France. The attitudes of these men undermined military authority and their refusal to serve in the army posed a serious threat. It is likely some member of the War Office wanted to make examples of the men by having them shot to discourage others from sharing their anti-war stance.

Scheduled Occupation and the White Feather Brigade

Some men were exempted from military service due to their occupation. These roles were described as ‘Scheduled (or reserved) Occupations’ and included coal miners, doctors, and those working in the iron and steel industries which produced vital ammunition and equipment for the war.

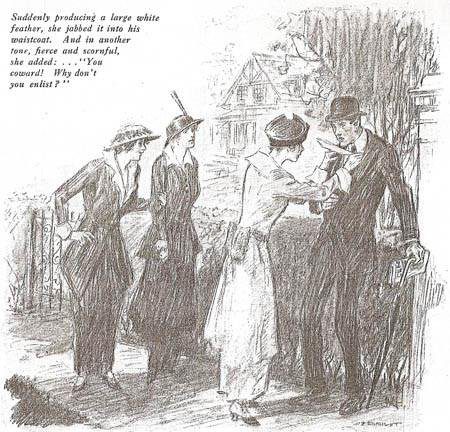

Some people believed such men were failing to fulfil their patriotic duties by not engaging in combatant roles, despite carrying out essential war work. The White Feather Brigade was born from these sentiments. It was an organisation established in Folkstone by Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald in August 1914, with the intention of increasing army recruitment. A Vice-Admiral serving in the Royal Navy, he was a strong supporter of the war and organised a group of 30 women to present white feathers to men out of army uniform to publicly shame them into enlisting. The idea spread across the country and men began to be pinned with the mocking ‘order of the white feather’.

The white feather became a widely recognised propaganda symbol, representing cowardice and pacifism. This meaning perhaps originated from the history of cockfighting, when a white tail feather of a rooster meant that the bird was considered inferior for breeding and lacked aggression. The symbol of the white feather was also used in a novel ‘The Four Feathers’ (1902), written by A.E.W Mason. The protagonist of the story, Harry Feversham, receives four white feathers as a symbol of his cowardice when he leaves his job in the armed forces and tries to leave the conflict in Sudan and return home.

Because of the activities of the White Feather Brigade, the government was forced to issue badges for men who were serving in jobs contributing to the war effort, known as ‘on war service’ badges. These were small, metal pin badges that were worn by civilians to indicate that the person wearing it was engaged in important war-work in the hopes of stopping any degrading treatment. Badges were created for occupations such as the railway service, war munitions volunteers, and those aiding to build HM ships and armaments. After conscription, the need for these badges lessened, along with the White Feather Campaign. However, many continued wearing them throughout the war, especially female factory workers as the badges could give priority boarding and fare concessions on public transport.